Ghosts in Your Genome?

Tuesday, March 6, 2012 at 11:12AM

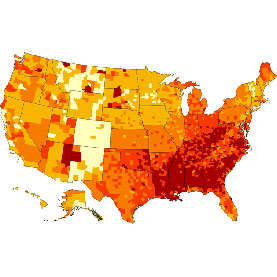

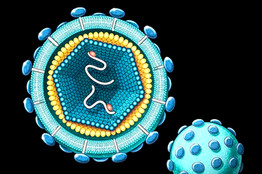

Tuesday, March 6, 2012 at 11:12AM The ghosts in your genome may be DDT (sprayed liberally in neighborhoods in the 1950s) or other chemical pollutants encountered by your parents or grandparents; or you may be passing along such ghosts from chemicals you encounter today. In new research at Washington State University the effects of environmental toxins were passed down to offspring, and even to second generation (grand-offspring if you will) of lab rats exposed to chemicals including jet fuel, plastics and the pesticide DEET found commonly in bug sprays applied to skin. The impact of the exposure was greatest in the first phase of pregnancy when gender is determined.

Earlier research from this team showed similar effects from pesticides and fungicides, but this is the first to show generational effects from a variety of environmental toxins. "We didn't expect them all to have transgenerational effects, but all of them did," Michael Skinner, the molecular biologist leading the research, told the technology website Gizmodo.

Earlier research from this team showed similar effects from pesticides and fungicides, but this is the first to show generational effects from a variety of environmental toxins. "We didn't expect them all to have transgenerational effects, but all of them did," Michael Skinner, the molecular biologist leading the research, told the technology website Gizmodo.

The study was funded by the U.S. Army to study pollutants that troops might be exposed to. Skinner and his colleagues exposed pregnant female rats to relatively high but non-lethal amounts of compounds widely encountered by the general public, and tracked changes in three generations of offspring. The results were disturbing.

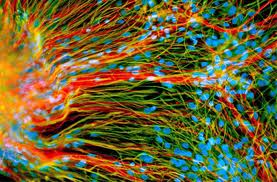

Researchers found distinct epigenetic signatures in the animals' sperm that acted as biomarkers of ancestral exposure to toxins.

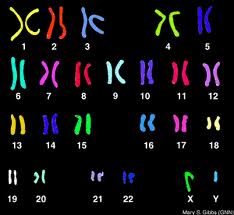

Toxins had a powerful effect on reproductive health. The researchers saw female offspring (and second generation offspring) reaching puberty earlier (particularly associated with exposure to plastics), increased rates in the decay and death of male offspring sperm cells and lower numbers of female offspring ovarian follicles that later become eggs. But there were also major implications for what is known as epigenetics, the science of how and why genes are expressed in individuals. The animal's DNA sequence remained unchanged, but the chemical compounds changed the way genes turn on and off, opening new ground in the study of how disease develops.

DEET,

DEET,  DNA,

DNA,  Washington State University,

Washington State University,  epigenetics,

epigenetics,  exposure,

exposure,  plastic,

plastic,  toxins

toxins

Reader Comments