Another Dirty Little Secret: Arsenic in Rice-Containing Foods from Organic Baby Formula to Energy Shots

Friday, March 2, 2012 at 9:35AM

Friday, March 2, 2012 at 9:35AM  Organic infant formula using organic brown rice syrup as a sweetener contained arsenic concentrations up to six times the EPA safe drinking water limitWe know that sometimes it feels like there's so much contamination in the food supply you can't eat anything. So please don't "shoot the messenger" of this alarming story. A new study (published last month in Environmental Health Perspectives, the peer-reviewed journal of the National Institute of Health's environmental arm) found high levels of the known carcinogen, arsenic, in foods that contain rice-based ingredients--especially organic brown rice syrup, used as a "healthier" alternative sweetener to high-fructose corn syrup. Rice ingredients are increasingly present in foods in part because people are looking for wheat alternatives (for example, 15% of autistic children in the U.S. are on gluten-free diets) and partly because the industry has worked hard to develop uses for its crops.

Organic infant formula using organic brown rice syrup as a sweetener contained arsenic concentrations up to six times the EPA safe drinking water limitWe know that sometimes it feels like there's so much contamination in the food supply you can't eat anything. So please don't "shoot the messenger" of this alarming story. A new study (published last month in Environmental Health Perspectives, the peer-reviewed journal of the National Institute of Health's environmental arm) found high levels of the known carcinogen, arsenic, in foods that contain rice-based ingredients--especially organic brown rice syrup, used as a "healthier" alternative sweetener to high-fructose corn syrup. Rice ingredients are increasingly present in foods in part because people are looking for wheat alternatives (for example, 15% of autistic children in the U.S. are on gluten-free diets) and partly because the industry has worked hard to develop uses for its crops.

Arsenic-based pesticides (which persist in soil indefinitely after application has ceased) were used extensively on cotton crops to control boll weevils, and today rice paddies routinely cover fields where cotton once grew.

The researchers at Dartmouth University in Hanover, New Hampshire analyzed foods containing rice ingredients (including rice flour, rice grains and rice syrup) from their local supermarkets, and identified arsenic levels above what's considered safe in drinking water. There are several areas of particular concern including rice syrups, baby formula, cereal and energy bars and energy shots. The study sites energy gels for endurance athletes listing organic brown rice syrup as a main ingredient (when consumed per manufacturer's instructions over a two hour workout) delivered more than the EPA limit for daily arsenic intake in water.

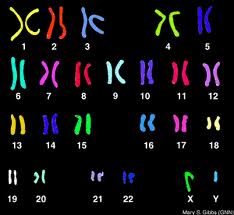

Perhaps the most mindboggling finding: "Organic" infant formula using organic brown rice syrup as a sweetener contained arsenic concentrations up to six times the EPA safe drinking water limit, and more than twenty times the arsenic concentrations in brown-rice-syrup-free infant formulations. Consider that safe drinking water limits are set for adults, and exposure per kilogram of body weight is two to three times higher for infants than it is for adults--the dangers are magnified for infants. Previous research suggests arsenic exposure in infancy can impact adult health; while it's difficult to connect the dots between environmental exposures and cancers that take decades to develop, it certainly seems ill-advised to feed a baby carcinogen-containing formula.

There are a number of issues at play that have created this alarming situation. One is simple lack of regulation. The United States only has a regulatory limit for arsenic in drinking water, not in food---so technically the food manufacturers delivering arsenic to your baby's formula are not breaking any laws. Organic certification requires soil that's been free of pesticide spraying for at least three years, but persistent contaminents including arsenic and DDT are allowed in organic soil (because they are impossible to remove.) The Dartmouth researchers conclude there's an urgent need for regulatory limits on arsenic in food. The U.K. and even China already have such limits in place, and this would seem like a very reasonable, if not essential, public health initiative.

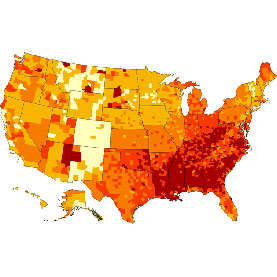

U.S. soil is a major factor. Rice absorbs more water than any other crop (at certain periods in its growth cycle rice must be submersed in water), and arsenic leaches into water from soil. The food industry loves to point out that arsenic occurs naturally in soil, which is true. However, southern soils in the U.S., where rice is commonly grown, contain higher levels of arsenic than occur naturally. Arsenic-based pesticides (which persist in soil indefinitely after application has ceased) were used extensively on cotton crops to control boll weevils, and today rice paddies routinely cover fields where cotton once grew.

In 2007, researchers found that rice from the south central U.S. (including from Arkansas, which produces half the rice consumed in the U.S; Louisiana; and Mississippi) contains nearly twice as much arsenic as rice from California (which produces 20% of U.S. rice.) The Dartmouth researchers also point out that a somewhat less toxic but still unhealthy metabolite of arsenic (known as DMA), which adds to the total arsenic concentration in rice-based foods, was used as a pesticide in the U.S. until it was banned by the EPA in 2009. Yes, Houston, we have a problem--and its right under our feet.

Paritcularly heart breaking for health fanatics is the finding that brown rice has higher levels of arsenic than white rice, though all rice contains small amounts of arsenic. The problem is in the bran layer that provides healthy nutrents and the rice's brown color. Unfortunately, arsenic is more concentrated in this bran (or "aleurone") layer, which is removed during the polishing process that creates white rice. Ironically, while there are more good nutrients in brown rice there is also potentially more toxic arsenic, depending on the soil and growing methods. Researchers at Cornell University and elsewhere are developing new less water-intensive growing methods as well as rice hybrids that absorb less arsenic.

Until the government and rice farmers sort out the arsenic problem, what can you do? Most importantly, do not use infant and toddler foods that list organic brown rice syrup on the ingredient label, and moderate your baby's intake of all rice. (Earlier research demonstrated that infants fed rice cereal at least once daily may exceed the daily arsenic exposure limit per kilogram body weight based on drinking water standards.) Secondly, check for organic brown rice syrup in your energy drinks, bars and gels; the body uses sugar to manufacture energy and these products tend to deliver high doses of it (commonly with organic brown rice syrup.) Other rice products, including rice flour and rice milk, and even just simply brown rice, should be eaten in moderation.

A simple blood test can check your exposure to arsenic. Ask your doctor to measure your level, and if it's elevated stop eating rice and rice products for a month. Then test it again, and see if the situation has improved. After you've cleaned out, proceed with caution in reintroducing rice to your diet.

arsenic,

arsenic,  energy shots,

energy shots,  infant formula,

infant formula,  rice

rice

Reader Comments