Deeply Troubling Evidence On the Dangers of Sleeping Pills

Saturday, March 17, 2012 at 12:11PM

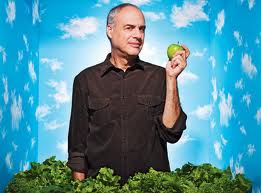

Saturday, March 17, 2012 at 12:11PM By Woodson Merrell, M.D.

A recent study published in the British Medical Journal (online) raised nightmarish questions about sleeping pills. The careful work that was done on this study demonstrates a strong link between sleeping pills and mortality (medical lingo for death), particularly from cancer. The study was meticulously designed (building on two dozen previous studies and taking into account pre-existing illnesses) and conducted by three physicians at Scripps Clinic, part of the University of California at San Diego and one of the nations' leading medical research centers.

A recent study published in the British Medical Journal (online) raised nightmarish questions about sleeping pills. The careful work that was done on this study demonstrates a strong link between sleeping pills and mortality (medical lingo for death), particularly from cancer. The study was meticulously designed (building on two dozen previous studies and taking into account pre-existing illnesses) and conducted by three physicians at Scripps Clinic, part of the University of California at San Diego and one of the nations' leading medical research centers.

People who took just three sleeping pills every two months tripled their risk of cancer.

More research is urgently needed to understand the trends uncovered by the Scripps researchers, but there is enough information in this five year retrospective study (meaning the researchers were analyzing existing data) to warrant much more caution in the use of sleeping pills than is exercised by most doctors and patients. Currently 10% of the adult population--tens of millions of people--are taking sleeping pills that may be exposing them to unnecessary cancer risk.

The study looked at a wide-range of sleep aids, including non-benzodiazepine hypnotics (such as Lunesta and Ambien), benzodiazepine sedatives (such as Restoril) and anti-histamines such as Atarax and Benadryl, which many people use in order to feel drowsy. Ambien and Restoril were associated with the highest levels of risk, but all of the pills were linked with increased risk of dying over the five years of the study.

The most prevalent risk of illness associated with sleeping pills was cancer: People who took just 3 pills every two months tripled their risk of cancer. Those who popped a sleeping pill twice a week increased their cancer risk up to 6 times. The risk of developing cancers of the prostate, colon and lung and lymphoma for people taking just two sleeping pills a week was higher than that of cigarette smokers. The other cause of death dramatically raised by sleeping pill use was suicide.

For the folks in this retrospective study, the more sleeping pills you took the worse your risk of dying, beginning at an average of a pill and a half a week. The highest risk level began at only two pills a week. In their conclusion the authors write, "Looking at all cause mortality--including depression and smoking--hypnotic use was the strongest risk [for dying] among men, stronger than cigarette smoking." They estimate that between 320,000 and 507,000 excess deaths in 2010 were due to sleeping pills.

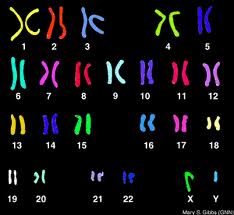

This is not the first time these questions have been raised. Studies as long ago as 1979 questioned the risk for cancer in people using sleeping pills. In that year The American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study I found cigarette smoking and sleeping pills were associated with excessive deaths. But the sleeping pill findings were discounted since the Cancer Prevention Study I was not designed primarily to study these drugs, according to the Scripps researchers. Since then 24 studies have examined sleeping pills and mortality, and 18 reported significant associations. The Scripps authors site evidence from at least one study that sleeping pills cause chromosomal damage

The Scripps researchers managed to take into account the fact that people who take sleeping pills are often more sick. To identify the effects of sleeping pills independent from pre-existing conditions the researchers exquisitely matched two controls to each subject with the same existing illnesses. They were also able to factor out for over 116 pre-existing conditions, including insomnia, which predisposes people to other health problems and is in itself a risk factor for illness, though, not for early death. If a 65 year old man taking sleeping pills smoked for 25 years, drank alcohol, had diabetes and insomnia, he was matched in this study with two men with the same profile who didn't take sleeping pills. In terms of retrospective studies, this one had a great deal of power in the statistical design.

Adding to the power of this study was its sheer size. It utilized medical records from the Geisinger Health System, the nations' largest rural integrated health system. The researchers looked at electronic records of 220,000 people over 5 years (from 2002-2007.) And then they looked for people to match up, whittling the group to be studied (the cohort) down to 10,000 sleeping pill users and 20,000 non-users. Over a five year period the people who took sleeping pills died more, especially as they aged. The average duration of patient use study was 2.5 years.

Sleeping pills were more dangerous with age, with dramatic differences beginning at age 65. Between the ages of 65 and 75, 8% of sleeping pill users were dead at the end of the 5 year period versus 1% of people who didn't take the pills. Over the age of 75, 18% of sleeping pill users were dead after 5 years versus 3% of the non-users. Younger folks made out better: of those taking pills from ages 18 to 55 just 2% died during the study compared to less than 1% of non-users.

Two of the biggest criticisms will be that the study is retrospective and that it did not look at every cause of death. They looked at all cause mortality, and then looked specifically at cancer and suicide, both of which were significantly higher for people on sleeping pills. The ethics committee overseeing the study did not allow the researchers to examine psychiatric illness. And alcohol use was not looked at in detail, people were divided into drinkers and non-drinkers, regardless of quantity. Both of those factors should be the subject of follow-up research; especially since many sleeping pill users die at night, when the combination of pills and alcohol can be fatal.

It's true that the study is observational, and therefore not as bullet-proof as a prospective, placebo controlled study that gives half a group sleeping pills and the other half a placebo under strictly controlled conditions. But the National Institute of Health won't allow a study that's designed to show something kills you faster. All cigarette studies are done with retrospective analyses. Or as the authors point out in their discussion, "the NIH won't allow a study on skydiving without a parachute."

The message for my patients: the older you get the riskier it is to take sleeping pills. At a young age if you use them on an occasional basis (a dozen a year) the risk is minimal. But more than that or older than that, especially with people at more risk for cancer or suicide, the risks become dramatic. This clearly shows sleeping pills are not meant for daily use, but for occasional insomnia. Patients over the age of 65 with cancer risk should find other ways to sleep.

The data from non-biased reviewers show there are meager benefits for sleeping pills anyway. In an article about the Scripps study, The New York Times points out that data from a large trial of Lunesta, reviewed by the F.D.A., showed that subjects slept 37 minutes longer than a control group, but got only 6 hours 22 minutes of sleep, and it still took them 30 minutes to fall asleep; it took the subjects on placebo 15 minutes longer. A study of Sonata had similar results, and 1 in 20 said they felt sleepy the next day while some reported memory problems. The risk/benefit of using sleeping pills as a regular sleep aid is simply not proven, especially in light of this new analysis.

Clearly other strategies need to be looked at the provide relief for sleep. The authors say cognitive behavioral therapy is the way to go - it's what's called sleep hygiene. One key is getting up at the same time every day until eventually your body forces you to go to sleep earlier. Other strategies include making changes to your sleeping environment, light therapy (getting full-spectrum light early in the morning) and using relaxation strategies before sleep or upon awaking in the middle of the night. In terms of getting off sleeping pills, regular users will likely have to taper the dosage. And I often encourage my patients to try herbal remedies such as valerian, amino acids L-tryptophane/5HTP, and/or melatonin.

If you take sleeping pills regularly it's time for a visit to your doctor to discuss stopping. Most every major medical center now has a sleep center (including the one run by the study authors) that provide analyses of your particular nights' sleep along with recommendation for how to make it better.

Reader Comments