`Shrooms To the Rescue!

Tuesday, February 3, 2015 at 3:40PM

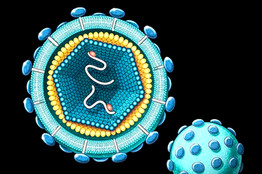

Tuesday, February 3, 2015 at 3:40PM With the CDC having declared a flu epidemic early in the season, and the flu shot only partially effective against the H3N2 virus currently circling the globe, we have become moderately obsessed with mushrooms as a weapon for neutralizing the viral threat.

Mushrooms of all varieties--including button, shitake and most powerfully maitake--contain numerous medicinal compounds with antiviral and antimicrobial effects. Most relevant to flu fighting are immune modulating long-chain polysaccharides found in abundance in mushrooms. Also helpful: the uncanny ability of mushrooms to increase Vitamin D levels.

Nutritional supplements containing mushroom extracts that concentrate the good stuff are most efficient at building the immune system, but the key compounds are notoriously difficult to isolate. Look for supplements like Immune Builder from JHS Natural Products, with pharmaceutical grade manufacturing and polysaccharide levels detailed on the label.

Then there's always the option to eat more mushrooms. Nutrition experts recommend buying organic mushrooms. As creatures of the soil, fungi tend to concentrate pollutants.

Our favorite new mushroom recipe works as a side-dish, or as a main course topped with even a simple protein like a poached egg.